The sun over Austin did that Texas thing where it gilds every edge—white roses blinking with heat, a ten-foot arch laced like a cathedral window, a live quartet testing a standard you could recognize in a single bar. Phones were lifted, champagne tilted, the skyline soft behind the oaks. The seating cards caught a breeze off Bee Cave Road and made a paper tide across the welcome table where a glass urn perspired with ice water and lemon slices. Our marriage license from Travis County lay double-checked in my clutch, folded beside a lipstick I didn’t need and the evidence I had promised myself I would never carry to an altar.

My name is Ava Carter. In an hour, I was supposed to be Ava Whitaker, wife to Liam—steadier than sunlight, kinder than rumor. If you asked for the story the way wedding magazines tell it, you’d get a spotless timeline: girl meets boy in a design showroom off South Lamar; boy asks about the antique hardware she’s already memorized; girl laughs; boy learns the word patina because she puts it in a sentence he wants to remember. Our families shook hands. The Whitakers brought their good silver and their better humor. My mother, Marjorie, brought lists. My stepfather, George, brought a watch he checked when no one was looking.

Everything was fine. Everything was beautiful. Everything had been rehearsed.

And then I saw her.

She stood a little behind the welcome table as if she knew choreography and had decided to honor it by staying just outside the dance. An older woman, small under the big live oaks, in a cardigan too warm for June. A canvas bag hugged to her ribs. Hair gathered back without vanity. The heat made mirages of everyone, but not of her. She watched the water pitcher the way a person watches a train that finally arrives on the platform you weren’t sure you believed in anymore.

“Ma’am, this is a private event,” the caterer said, gentle but firm, palm hovering midair like a crosswalk signal.

The woman nodded the way people nod when they’re used to shrinking their needs into something that won’t trouble anyone. She took a half step back. Then a half step forward. The words left her mouth like a thread—fine, true, easily broken by a stiff wind.

“Could I please have a sip of water?”

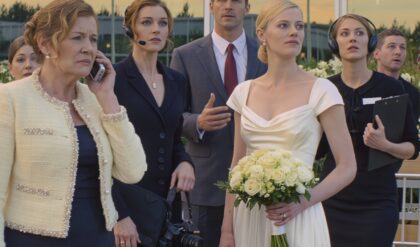

The quartet lifted into the melody again. Liam squeezed my hand and made a joke about summer, and I smiled on instinct. It was what the day required: a practiced, camera-ready smile. I reached for a glass—crackle of ice, lift of lemon—and turned to find his eyes so we could fix this one more memory like it belonged to everyone.

Then I looked back over my shoulder and really saw her face.

The glass slid from my fingers. It touched the stone and didn’t shatter so much as become a bloom of light—harmless stars skittering under the table.

“Are you okay?” someone said.

I nodded because nodding was easier than admitting that time had tilted. The quartet seemed to fold into its instruments. Laughter flattened into a single hush that moved through the rows like wind through wheat. Even the roses held still, as if the garden itself had taken an oath not to breathe.

My mother’s smile tightened, curator-sharp. “Ava?” she said, as if she could call me back by using a museum voice in a field.

But I was already moving.

I crossed the lawn the way you cross a room in a dream—faster than you remember deciding. People made space in that very American way, polite and curious and pretending not to stare. A loop of red-white-and-blue bunting from last night’s rehearsal barbecue had come loose from the lemonade tub; it brushed my dress like a small wave.

Up close, the woman’s hands trembled—not from fear, but from relief. It made my throat burn. The sun had written the years across her forehead with unembarrassed precision. The cardigan was clean. The canvas bag was darned where it had failed and mended by someone who believed things deserved more than one chance.

“Let me,” I said, and signaled the caterer. He arrived with a fresh glass and a slice of lemon that looked too proud for its purpose. I took the glass, and she took my hand with it, because there are moments when you need the human part of the transaction more than the object you came for.

Her fingers brushed mine; a room I hadn’t stood in for twenty years opened behind my ribs.

Popcorn ceiling. A floor fan like a helicopter. A light under a door. Me, counting faint constellations in plaster and stopping at seven because seven felt like a promise.

“I know you,” I said. The words were steady when they left my mouth. “And you know why I’m here today.”

She blinked—once, slow. Then she nodded. Not a plea. Not a demand. A recognition, the kind you make at a door you thought would stay locked and find open instead.

“Ava,” my mother called, too bright. “Honey, the photographer—”

Liam touched my shoulder. “Do you want me with you?”

“Yes,” I said, without looking away from the woman. “But first—water.”

She drank as if it were a ceremony: both hands, careful, present. When she finished, she held the glass like an artifact. The quartet found its key again. The officiant checked his watch. Somewhere beyond the hedge, I-35 sighed—a long ribbon of cars pulling their own stories past ours.

I knelt so my hem wouldn’t catch gravel. My voice felt like it belonged to a younger version of me, a girl who wrote letters she didn’t send and kept a small shoebox of proofs in the back of a closet like other girls kept summer dresses.

“It’s you, isn’t it?” I said. “From the photograph.”

The woman’s eyes lit the way a porch light does when it recognizes footsteps. “It’s been a long time,” she said.

“What photograph?” Liam asked, softly.

“The photograph in my shoebox,” I said, still looking at her. “A porch with one rotten step and geraniums in coffee cans. A woman with a strand of hair across her brow. A girl on her hip with a birthmark behind her left ear that looks like a comma. I have the photo. I have the comma. I have the note that says, ‘Ruth, you did right to keep her safe.’”

The woman—Ruth—closed her eyes, and I watched a decade of waiting slide behind her eyelids where it could stop standing guard. When she opened them, there was no demand in her gaze, only the quiet power of a person who knows that truth doesn’t need volume to be heard.

My mother arrived, linen whispering, pearls anchored exactly where they should be. “Ava, sweetheart,” she said, smile poised for guests, voice pitched for me alone, “we can take care of refreshments after the ceremony. This area is… we should keep it clear.”

Liam stepped between us with the gentleness that has always been his way of drawing a line. He didn’t raise a hand. He didn’t raise his voice. He turned to Ruth and offered what should have been offered first.

“Would you sit?” he said, pointing to a shaded chair near the welcome table. “If you’re comfortable, you’re welcome here.”

Ruth looked at him as if she was measuring the words, not the suit. She nodded and took the chair. When she sat, she did it like someone easing into a pew—a small, deliberate devotion.

“What is this?” my stepfather asked, arriving from nowhere the way certain men appear when they sense a moment they can reorganize. “Ava, do you need security?”

I stood. The heat stitched itself into my spine. I looked at him, at my mother, at the guests who had been trained from birth to pretend nothing unusual is happening in front of them until it becomes impossible to pretend. I looked at the quartet, which had stopped again without instruction. I looked at the bunting, at the sunlight, at the glass on the ground that had become stars and then just glass again.

“No,” I said. “I don’t need security.”

I reached into my clutch and pulled out the things I had promised myself I would never need to show anyone, least of all today.

A photocopy of a letter—ink blotched, date legible: July 14, 1997. A library card with a name half rubbed off: Ruth El—. A bus stub from Killeen to Austin, two corners missing as if someone had worried them back when worry was a way to stay awake. A Polaroid where the light had turned to honey at the edges.

Receipts, people call them, when they want proof you can hold. I laid them on the welcome table where guests had been placing gifts in a copper box, their envelopes fat with cards that would make good memory but not good evidence.

I spoke so the garden could hear me. If I had a microphone, I would have used it, not to amplify the drama, but to move the truth past lips and larynx into air where it could stop being mine alone.

“My last name is Carter,” I said, “because I grew up in Marjorie’s house with George’s keys on a hook by the door that I was told not to touch. Before that, my life is photocopies and guesswork and a photograph that never learned how to fade. The story I was given is pretty. It’s clean. It’s the kind of narrative that looks right framed on a wall. But pretty and clean are not the same as true. I don’t say this to undo anyone’s kindness. I say it so I can breathe the same way everyone else breathes.”

My mother tried to take my hand. I stepped half a step back, not to accuse, but to get enough air to finish.

“When I was little,” I said, “there was a lullaby that didn’t match any my mother knew. It came into my head like a melody from a radio down the block. When I couldn’t sleep, I hummed it to myself, and the world felt less like a room with no windows and more like a porch with geraniums and a woman whose hair wouldn’t stay where she pinned it. Two years ago, I found a box in the attic with papers that didn’t belong to any official version anyone had ever told me. I wrote letters. I waited. I listened. And this morning, on the day I was supposed to become a wife who had no questions left, I felt the kind of certainty that makes you put fragile things in your clutch anyway. I didn’t plan this. I didn’t invite this moment. It came like weather we should have checked the forecast for but didn’t.”

George’s mouth kept the shape of a smile long after his eyes had given up. “Ava, darling,” he said, “this is neither the time nor the place.”

“This is exactly the time,” Liam said, not to argue, but to agree with me out loud in case my courage needed to borrow some of his. He turned to Ruth. “Ma’am, I’m Liam. I’m the man lucky enough to marry Ava. If you’re the person she believes you are, then you’re my family, too. Can we get you anything besides water? Shade? A seat closer to the front?”

Ruth’s gaze slid to my clutch where the Polaroid lay like a small door you could open with a fingernail. She touched the edge of it with the same care she had used with the glass.

“My name is Ruth,” she said. “I don’t come to take anything that belongs to someone else. I came to look. Just to make sure that what I told myself was true—that she was fine, that she made it, that the little mark behind her ear is still there and not just something I invented so I could sleep.”

I lifted my hair without thinking. The comma at the base of my skull had traveled with me all this time, a punctuation mark that meant keep going, don’t stop yet.

“She kept me safe,” I said, half to the guests and half to the part of me that had been six for so long. “She kept me safe in a way stories never make room for, because stories like tidy rooms and this isn’t one.”

Someone near the back clapped once—the polite, startled kind of clap that says a person’s hands are faster than their self-consciousness. Then another. Then silence again, because nobody knew the script.

“I didn’t come to interrupt,” Ruth said. “I don’t want any trouble. I saw the water and… it’s hot. I thought I could ask. If I’ve made anyone uncomfortable, I can go.”

“You’re not going anywhere,” I said. “You’re staying. You’re sitting in the front row. And when the officiant asks who presents the bride, I want the answer to be all the people who kept me alive long enough to stand here.”

Marjorie’s face softened then—really softened, not the kind that looks like soft for photographs. She blinked fast, the way you blink when you refuse to let tears steal your vision. “Ava,” she said, her voice smaller than I’d ever heard it, “I should have told you more. I thought I was protecting you. I thought… I was protecting us.”

George put a hand on her elbow, and she shook it off. He looked surprised, like a man who has trained a household to anticipate his moves and finally finds himself playing against someone who declines to lift a piece until she’s ready.

“I won’t let today be about what we didn’t do right,” I said. “I want it to be about what we do next.”

Liam cleared his throat. “May I make a suggestion?”

I nodded.

He turned to the quartet. “Would you mind taking five? We need a tiny family meeting. Everyone, grab some lemonade. There’s plenty. We’ll begin again in a few minutes.”

It takes a specific courage to announce a pause at a wedding. People love a schedule; it makes them feel like the world is in good hands. But the guests shifted in that cooperative way the best of them do, like a school of fish agreeing to turn all at once. The officiant closed his book. The photographer eased his camera down and let the strap take the weight.

We stepped into the shade of the oak closest to the arch—me, Liam, my mother, George, and Ruth with her canvas bag, which she kept close as if it were a heart in another form. The bunting fluttered once more as if it had one last opinion and then settled.

“Tell me everything,” I said to Ruth. “Tell it the way you need to. We’ll listen.”

She looked at the ground for a long beat, not to collect herself, I think, but to honor the earth that had carried her here. When she spoke, the words were clean and simple, not because the story was simple, but because the only way through a thicket is one step at a time.

“I was nineteen,” she said. “Very sure of the wrong person and very unsure of everything else. There was a church off FM 2222 where they didn’t ask many questions when you went for a paper bag of groceries. The pastor’s wife knew me by name. When you were born, I did what made sense with two dollars and a bus route. I knocked on a door I had been told was kind, and I asked someone to hold you while I tried to become someone worth bringing a child home to. I came back with a job application and a bruise I couldn’t explain, and the door didn’t open. The pastor’s wife said the family had stepped in, that you were safe, that I should get safe, too. I told myself those were good words. I left a note. And I told the Lord if He let me see you again once you were grown, I wouldn’t ask for anything. Not a dollar, not a day. Just a look.”

She shrugged like a person apologizing to the wind for being in its way. “I didn’t expect the look to happen on a day this beautiful.”

My mother put a hand to her mouth. When she dropped it, a sound came out that didn’t belong to any polite register she kept on display. “We were told you had decided… that you had signed… that you didn’t want… I’m sorry.”

Ruth nodded. “Sometimes the words people use are tidy. Life isn’t.”

George cleared his throat, businesslike. “In any case, we’re here now. We have a ceremony to get back to. We can sort through the rest later.”

“No,” I said. “We’ll sort through the rest now, or at least enough to make ‘later’ stop feeling like a door we’re trying to hold closed with a chair.”

I looked at Ruth. “Do you have anything… anything you kept?”

She reached into the canvas bag and brought out a locket the size of a nickel. Half a heart, cheap metal, initials scratched with something that couldn’t decide if it was a needle or a nail: A.C. on one side, R.E. on the other, a hinge that had learned the language of stubbornness.

I reached into my clutch and brought out the match.

The click it made when the halves met could have been a mistake if you weren’t listening for it.

Marjorie put her fingers to the locket like a woman reading braille on a fragment of a story she had told using prettier nouns. “I didn’t know,” she whispered. “Ruth, I didn’t know.”

“You did what you thought you should,” Ruth said. “I did what I could. Maybe today we all get to do what’s right.”

Liam took a breath that sounded like a man choosing. “Then this is what we’re going to do,” he said, eyes on me as if I were the only person he needed to convince. “We will invite Ruth to the front row. We will acknowledge her the way we should have from the first moment she asked for water. We will pause again later to eat, and anyone who wishes to give a toast will give one. The first will be to the people who kept Ava standing. After today, we’ll set a meeting—with all of us—and we’ll go to the county, and if there’s a way to unseal anything that belongs to Ava, we’ll do it, and we’ll follow the law and her heart in that order. In the meantime, this is our wedding, and our vows include making room.”

He turned to my mother. “Marjorie, I love your daughter. That won’t change with a single new fact. It only grows. Will you stand with us?”

Marjorie nodded, tears open now, not negotiating with them anymore. “Yes,” she said. “Yes.”

“George?” Liam said.

George’s jaw worked, then settled. “Do what you will,” he said, which is the kind of surrender a certain kind of man manages when grace arrives in a form he doesn’t recognize. It wasn’t approval. It was absence. It would have to do for the next ten minutes.

We walked back into the sunlight. The Quartet waited for a cue. The guests, held in a soft suspense, turned toward us with relief and curiosity balanced like eggs on a spoon.

The officiant lifted his book. “Shall we begin?” he murmured.

“One thing first,” I said, and put the locket halves together in my palm. “This is my wedding. I want to welcome someone before we start.”

I looked at the chairs near the aisle and then at Ruth. “Would you sit here? Next to my mother?”

A murmur went through the crowd, not gossip, not judgment—a kind of gratitude, as if a room had just had a window opened that no one realized was painted shut.

Ruth hesitated. Marjorie stood and held out her hand. The gesture was brave; it trembled anyway. Ruth took it. They sat shoulder to shoulder, two women whose lives had braided around mine without ever agreeing to meet.

The quartet began, cautious and then confident. The officiant spoke the words that make people cry even when they claim they are impervious to that sort of thing. When he reached the question about who presents the bride, Liam answered before anyone else could.

“All of us,” he said. “Everyone who kept her safe. Everyone who loves her. Everyone who learned something about water today.”

Laughter moved through the chairs like a sigh that had remembered how to start again. The ceremony unfolded. Vows that had sounded good in a kitchen sounded better in the open air. Rings found hands. A hawk cut a line across the hot blue like a signature, and for a long moment no one moved because they were so busy letting relief become joy.

Only then did the quartet slide into something that would’ve been corny on a lesser day and felt perfect now. The photographer lifted his camera and caught the exact second Ruth wiped at her cheek and tried to pretend she hadn’t.

At the reception, we did what people do when the official words are done: we ate and talked and pretended our shoes were smarter than our feet. The Whitakers have money without the habit of bragging about it; their toasts are always stories, never résumés. Harrison told the one about Liam learning to fix a broken cabinet hinge by watching a ten-minute video and then starting a company six years later that did nothing in ten minutes because precision requires time. Claire told the one about me hunting down a antique doorknob that matched a set of original locks like I was chasing a clue in a case the city had forgotten. “You should’ve seen her spreadsheet,” she said, lifting her glass. “That thing had footnotes.”

People laughed. People wiped at their eyes. People glanced at Ruth and then away and then back again, the way you look at a landmark you want to memorize—a way of telling yourself how to get home.

When it was my turn, I didn’t tell a story. I made a promise.

“We’re starting a thing today,” I said into the microphone, the locket warm in my palm like a small, obedient heart. “It’s simple. It’s not a foundation, not yet, not in any legal or impressive sense. It’s a pledge. Every event our family hosts—even if it’s just a backyard cookout—is going to have a table that faces the world, not just the guest list. Cold water. Shade. A chair. No questions asked except the kind that make someone feel human. We’ll call it the Ruth Table. If this is the only thing we ever do right as a family, then we will still have done something right.”

A whistle—quick, grateful—cut through the applause. I followed the sound and found the waiter from earlier standing by the lemonade tub, his hands already busy re-arranging cups without being told. He caught my eye and nodded. It was apology without theater.

Then Liam lifted his glass. “To Ruth,” he said. “To Marjorie. To the comma behind Ava’s ear that taught us where to pause and where to keep going.”

When the dancing began, I left my shoes under the table and let the grass instruct me. Liam spun me once, the quartet took a risk that paid off, and our friends formed a circle the way good friends do when they want to prove geometry can feel like love.

A while later—after barbecue that deserved its name, after a slice of cake that was better than any policy about cake, after three songs that made even George smile because the saxophonist wouldn’t let him not—I noticed Ruth standing by the rope lights. She wasn’t apart, exactly. She was doing what I’ve seen careful people do in rooms where joy takes up a lot of space: measuring her presence so it wouldn’t bite into anyone else’s share.

I went to her. “Dance with me?” I said.

She laughed, surprised. “I’m nobody’s idea of light on my feet.”

“You’re mine,” I said, and took her hand.

We didn’t dance much. We swayed. We counted a few steps that matched an old lullaby, the one I had hummed to myself without understanding who had put it there.

When the night folded itself into goodbyes, Ruth stood near the edge of the lawn with her bag. She looked at the water pitcher, now more lemon than ice, and shook her head as if a single sip had been enough for the day.

“Do you have somewhere to sleep?” I asked, keeping my voice easy so it would land like an offer and not a spotlight.

“Yes,” she said. “I help out at a church off Manor Road. They keep a room for people who need one, and I try to be someone they’re glad took up the space.”

“Tomorrow,” I said, and didn’t give her a chance to interrupt, “you’re coming to brunch. Not because it’s the kind thing. Because it’s the true thing. We’ll start there and go one day at a time, and if the days begin to look like a life, then we’ll be doing it right.”

She nodded. “One day at a time sounds about perfect.”

Liam walked up with a to-go box of brisket he had packed with the seriousness of a man who believes food is a promise, not a plate. “For later,” he said. “And for the walk.”

Ruth took it like it was flowers. “For the record,” she said, “you picked a good one.”

“I know,” I told her, because there are moments when humility is dishonest.

We left under a sky that had finally given up on being afternoon. The bunting tugged once more like it wanted to travel and then stayed, loyal to its string. Someone tucked sparklers into my hand. I lit one and wrote my new last name in the dark: not to replace what I had been, but to add to it.

The next morning—late, because joy takes muscle—we all squeezed around a table at a diner on South Congress that hadn’t changed its menu since the year the waitress was born. Ruth ordered coffee and drank it in tiny sips as if it were a story she wanted to last. Marjorie brought a photo album because some people apologize by telling you everything they should have told you fifteen years ago and then giving you the evidence that they should have told you.

George arrived because he was a person who still wanted to be present in his own life. He sat at the end of the booth, reached for the salt, and then rested his hand on the table like he had changed his mind midway through a habit.

Liam sketched on the back of a receipt because that’s what he does when a plan starts to make itself available to him. “A house,” he said, eyes on the lines his pen was drawing. “Not a big one. East side, something with a porch. We can help. Not as a prize. As a place. We’ll call it a loan if that makes it easier for everyone, and we can argue later about how loans feel like gifts when you don’t ask for the balance every five minutes.”

Ruth listened. “I won’t be a burden.”

“You won’t,” I said. “You’ll be a person with a key.”

We found the bungalow a week later. It sat one street back from a community garden where the scarecrow wore a scarf in winter and a ball cap in July. The porch had room enough for a chair. The chair had room enough for a glass of water and a book. We spent a Saturday washing windows and another Saturday convincing a stubborn lock to trust us. The third Saturday, Liam hung a small flag from the rail—no flourish, no speech—just a quiet promise that this address belonged to a map bigger than one family’s confusion.

Ruth moved in like a person accepting a coat she hadn’t expected to need again. She kept the cardigan she wore the day we met. She hung the locket from a nail over the kitchen light switch where it caught morning like it had a right to.

The meeting at the county clerk’s office was not dramatic. The clerk had seen more TV than any of us and wasn’t impressed by the notion of a story that might sell ads. She was very impressed by forms completed correctly and IDs that matched signatures and patience used without sarcasm. We filed what we could file, requested what we were legally entitled to request, and promised to return with exactly the papers we were missing and not one sheet less. That’s how a lot of justice happens in America—quiet rooms, good pens, a willingness to sit without flinching while systems prove they can be human if you stay long enough.

The unsealed record, when it came, did not rewrite history. It put names where blanks had been. That is sometimes enough. Marjorie cried when she saw the page. “I wanted to be the only mother,” she said, and then shook her head. “No. That’s not right. I wanted to be enough. I didn’t know how to share being enough.”

“You were enough,” I told her. “And so is Ruth. The math isn’t subtraction. It’s the kind where you add a room and the house doesn’t fall down.”

George left early from that meeting, muttering about calls. He sent a text an hour later that said, I’m trying. It wasn’t the apology I dreamed of, but it was a sentence I hadn’t expected to read with his name under it. Sometimes the truest change in a person is the punctuation. He’d chosen a period instead of a justification.

The Ruth Table became an actual thing by the end of the summer. It was a folding table at first, then a custom build Liam designed with a canopy you could crank with one hand and four shelves that kept cups where people could reach them without feeling like they were taking the last one. Friends copied us. Then strangers did. A photo from a wedding in Boise showed up in my inbox with the subject line, “We did it, too,” and a note that said, “We met a man who came for water and stayed to hear the vows. He cried during the father-daughter dance and didn’t try to hide it. Thank you.”

There were days we got it wrong. A volunteer asked someone a question no one should ever have to answer to drink a glass of water. I apologized with my whole chest and wrote our pledge out on a laminated card we zip-tied to the underside of every table: Water, shade, a seat. No questions. If we have socks, we offer socks. If we have sunscreen, we offer sunscreen. If you want conversation, we’re here. If you want quiet, we’re here. If you want a place to sit where no one will stare, we’re here.

Autumn softened the edges of the city without making it forget it lives in Texas. Ruth kept a schedule that pleased her: mornings on the porch, afternoons at the community center where she read to any child who brought her a book and a juice box. On Wednesdays, she came to our place and ate soup as if soup were evidence that stew can be refined if you’ve got time and a willingness to use low heat.

On Thanksgiving, we set a long table in our yard and invited every person whose name had been part of our summer. The Whitakers planned sides the way architects plan roofs: for shelter. Marjorie brought pies and a laugh that came from somewhere deeper than manners. George arrived and did not stand at the edge. He poured water for people he didn’t know and didn’t ask them to tell him who they were before he offered seconds.

When it was time for the toasts, no one stood on a chair. We didn’t need height. We needed honesty.

“I messed up,” George said, surprising himself most of all, I think. “I cared about the picture more than the frame. That’s a designer joke, I guess.” He gestured at Liam, who groaned, relieved to be teased. “Look, I—no, let me start over. Ruth, I’m sorry for not making space faster. Ava, I’m sorry for asking you to be small. Marjorie, thank you for telling me to sit down in the middle of a field and listen.”

People clapped like they were encouraging a shy animal to come out of a stand of pines. Ruth lifted her glass of iced tea and nodded the kind of nod that forgives without making a parade out of it.

Later, near midnight, when the dishes were stacked and the last friend had taken a container of leftovers because saying no to kindness is a worse sin than refrigerating too little, Ruth and I sat on the porch of her bungalow. The flag on the rail moved like breath.

“Tell me about the lullaby,” I said.

She sang three notes, and I finished them. We stared at each other like a magic trick had worked not because it was clever, but because it had always been true.

“What would you have named me?” I asked.

She smiled at the question as if it were a key she had kept on a hook by the door a very long time. “Ava,” she said. “Short for avois—no, I’m teasing. For breath. For life. For the sound you make when you finally set something down.”

I leaned my head against the frame. “Then we did it right.”

Winter finally made a polite show of itself in Austin, which means you need a jacket for about three hours a day and the city behaves like a person who has to pretend it owns a coat. We kept the Ruth Table running with thermoses that steamed when you opened them. We added a basket of knit hats some grandmother in San Marcos dropped off with a note that said, “For heads that need them.”

The clerk called in January to say a document had arrived we might like to see together. We met at the office with the bad fluorescent lights and the good pens. The paper had my name at the top and Ruth’s on a line that had been blank in every version before. There was no ceremony. No trumpet. Just a stamp, a nod, and the feeling you get when a piece slides into a puzzle and the picture becomes something you can make sense of.

Marjorie squeezed my arm. “I will never be threatened by another person loving you,” she said. “I might be jealous sometimes. But not threatened.”

“Jealousy is just love that needs a glass of water,” I said, and she laughed through tears. “We’ve got a table for that.”

In the spring, the community center asked if we would mind if their new reading room bore a name. We said yes before they finished the sentence. They called it the Harper-Carter Room, because Ruth had been Ruth Harper before the years moved her into a future where names have to learn how to carry more than one meaning. The plaque didn’t boast. It simply told the truth: In honor of the people who make room.

One night, months after our wedding, I woke to a sound that wasn’t quite thunder. Liam slept on, because he is the kind of man who trusts the world to be as gentle as he is. I slipped out of bed and went to the window. Rain had started the way a story starts when everyone thinks the page is blank. It pattered, then steadied, then blurred the street until the porch light turned into a halo that didn’t belong to a saint so much as to anyone who had ever waited on a step for a door to open.

I thought about the glass that had become stars and then a lesson. I thought about a locket that had been two halves pretending to be complete. I thought about a woman who asked for water and got a family, and a family that asked for grace and got a table.

When the rain let up, I made tea and sat on the floor where the light likes to land in the morning. I wrote a note on the back of a photograph the way somebody once had. I wrote it to the girl I used to be, to the woman I was, to the child I might one day know by name. It said:

You are not the story someone tells about you to make their own life easier. You are the story you step into when your hands are steady enough to hold a glass and your voice is strong enough to say please and thank you and I’m here. The door you are waiting for is real. If it doesn’t open, there is another one, and another, and another, and sometimes the knob is a hand held out to you with a small locket in it that clicks when you close your fingers.

I signed it with both my names.

In June, on our anniversary, we went back to the garden. The arch had been taken down. Another couple would use it, or it would become something else entirely, because that’s how wood and promises work if you treat them with respect. The oak was still there, generous as a grandparent. The bunting was gone—only the hook remained, a small conversation between metal and bark.

We set a table. Cold water. Shade. A chair. We didn’t publicize it. We didn’t need to. A jogger stopped and drank and said nothing except, “Man, Austin, right?” A kid on a scooter asked if he could sit while his mom retied a shoelace. A man in a suit stood for a long moment with his eyes closed and then opened them and met mine and nodded like he had decided to keep going after all.

Ruth arrived last, carrying a grocery store bouquet like it was as fancy as anything on a magazine cover. She handed it to me. “For your house,” she said. “For the room you added.”

We hugged the way people hug when they know they’re not fixing anything and don’t have to.

Justice doesn’t always roar. Sometimes it looks like a glass of water given when asked. Sometimes it looks like a woman stepping across a lawn because she recognized a face from a photograph kept under receipts and a lipstick. Sometimes it looks like a man who says, “We’ll begin again in a few minutes,” and means it. Sometimes it looks like two halves of a locket agreeing to be a whole without erasing the seam.

Our wedding wasn’t perfect in the way magazines like. It was right in the way life needs. We said vows. We kept them. We made room.

And whenever I pass the Ruth Table at any event we host—whether it’s a barbecue or a book club or a birthday for someone who swore he didn’t want a fuss—I run a finger along the edge of the canopy crank and feel the way it has been used by hands that aren’t mine. The surface is smoother now. That’s what happens when something belongs to more than one person. It gets better at being itself.

If you come by, there will be water. There will be shade. There will be a seat. You won’t have to explain who you are to be welcome. We’ll ask your name only if you want to tell it. We’ll remember it if you do. And if you don’t, that’s fine, too. Some stories take a minute to say out loud. Some doors need two knocks. Some hearts need the soft click of a hinge remembering it can move.

We’ll be here. We’ll keep the glasses clean and the ice fresh. We’ll keep adding rooms until the house we live in is big enough to fit everyone who needs a place to sit down and breathe.

That’s our promise. That’s our beginning. And if anyone asks how to do it, we’ll hand them a cup and say, “Start with water. The rest will follow.”