The notary’s stamp clicked like a gavel and his mother smiled as if she’d won a raffle. “This is Adam’s house,” she said, tapping the signature line the way people tap a fish tank, testing the glass. “If things don’t work out, you’ll leave with what you brought.” Behind her, the late Pacific light washed La Jolla a forgiving gold—palm fronds, clean stucco, a strip of flag on a neighbor’s porch lifting once in the ocean breeze. I signed because I was in love, because a page with margins and a seal can look harmless when someone you love is nodding. I signed because I believed character could outlast paperwork.

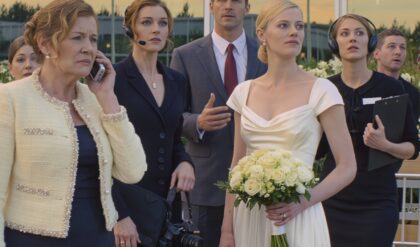

We married on a Saturday that smelled like sunscreen and eucalyptus. The ceremony was small—friends from my software team, two of Adam’s cousins, a pastor who knew the right length for vows. Afterward, I carried my dress through a narrow hallway while the ocean kept knocking at the edge of the day, the way it always does in San Diego. His mother hugged me stiffly; his father shook my hand as if I were a vendor who’d met a deadline. We drove away with confetti clinging to the bumper and the house key—their house key—glinting on Adam’s ring.

I had been fine before Adam. I had a one-bedroom near Balboa Park where I could hear the organ concerts on Sunday afternoons if I left the windows open. I had a pass for the gym tucked beside the Little Italy trolley stop and an accountant who reminded me every April that I was ahead of last year. I wrote code that shipped on time. I collected city library receipts. My fridge was a philosophy: eggs, spinach, almond milk, a pitcher of cold brew, a jar of strawberry jam labeled in a neat black Sharpie because I like things I can name. I wasn’t rich, but my life fit, and when something fits, you don’t notice the seams.

Adam’s life had seams made of other people’s thread. His parents, Evelyn and Richard, ran a real estate company that had been building in Southern California since people wore white gloves to open houses. They had opinions about everything: flooring, the economy, the correct number of olives in a martini, the right sort of woman for their only son. They didn’t say those last words out loud, but they never needed to. The first time I ate dinner at their house, the table was set with something that had probably been shipped from Italy. Evelyn asked about my degree, my parents, my “plans.” Richard asked for the salt.

There are a thousand small ways to tell someone they don’t belong, and they tried most of them. I wore black pants to a barbecue once; Evelyn tilted her head and asked if I had a funeral after. When I brought a pie for Thanksgiving, Richard asked how much time I’d spent at the store. It was always little comments, little digs, a steady rain of tests you’re not supposed to notice. I endured because Adam sent me midnight texts that made my sternum soften, because he touched the small of my back when he passed behind me, because he said he’d chosen me.

The prenup didn’t hit like a betrayal because betrayals are sharp, and this was the dull, practiced shape of money arranging itself. “It’s standard,” Evelyn said, that night at the walnut table. “Protects the family, protects you.” She poured a measured inch of wine. Adam cleared his throat, pushed his plate away, and found a whole coastline to stare at out the window. The document said the house in La Jolla was Adam’s separate property. It said his inheritance would be his if it ever arrived. It said I wouldn’t be entitled to assets that weren’t mine. There was a section—small, tidy, the kind of paragraph most people would skim—that defined separate property on both sides. And the notary waited.

The first year, we were tender. We walked to the cove at dusk. We bought a cheap pair of binoculars at a tourist shop because Adam swore he’d seen a blue heron on the rocks and wanted proof if it returned. I built a shelf in the laundry room and he told me I was a magician because the drill never bucked in my hands. There was an American flag on the next-door patio that made a crisp sound when the wind changed at night; we could hear it if we left our bedroom window cracked. We made a life within someone else’s house. It worked because I believed work could make anything fit.

Year two grew quiet. Adam stayed late at “meetings” and came home glossy with the kind of charm you put on like cologne. He loved the kind of sentences that began with “my accountant says” and ended with “write-off.” His parents treated our weekends like a series of optional inspections. “We’re stopping by,” Evelyn would text, thirty minutes after she and Richard had found something they needed to stop by for. She’d lift a pillow from the sofa, set it down, and call it a comment. Richard would ask if I’d considered a different stain for the kitchen island.

By year three, the temperature changed. It’s not that Adam stopped loving me; it’s that he stopped choosing to. Love is a decision people think is a feeling. He started asking if I was “sure” about my outfit before we went out. He suggested a dermatologist with the kind of voice that isn’t quite a suggestion. He began to use the word dramatic as if it were a synonym for female. In the morning he’d leave me with a kiss and a to-do list I hadn’t asked for. At night he’d hold his phone a little closer to his chest.

My uncle died in the middle of a regular day. I was eating an apple at my desk when my mother texted and said to call her, and the older I get the more I understand how often grief arrives at our desks, in our cars, in the cereal aisle, anywhere there are fluorescent lights and receipts. We weren’t close, my uncle and I. He lived back east, in a way that was always “back east,” even when the map said a specific state. He’d been a careful man—banker careful, leather ledger careful. When the letter about his estate arrived, it wore a bank’s letterhead and a spine made of staples.

Twenty-two million reads like a typo, then like a test, then like a mirror you try not to step in front of too quickly. I read the number twice, then the cover letter again, my heartbeat a drum line in a room that smelled like toner. The trust was real. The schedule was simple. The distribution was wire-ready. I walked to the parking garage and sat in my car and listened to somebody on the radio report a three-car accident near the 5. The world did what it always does: continued.

News travels faster in families than heat in a small kitchen. By the next weekend, Evelyn had ideas. Lunch at a place in La Jolla Village where the menu pretends calories aren’t a noun. She smiled a smile that pressed two lines beside her mouth and said, “We should think about an advisor.” Richard, who had never asked me about my work in any substantive way, suddenly wanted to know if my company was hiring because he “has a young associate” who “understands technology.” Adam held my hand like a campaign photo.

I let them talk. I let them toast. I let them say “we” in a way that included my name. I let Adam say things like investment property and family enterprise and portfolio—not because I agreed, but because I needed them loud. People tell you who they are when they think you’re not listening.

I made an appointment with a family law attorney on Fifth Avenue who wore her hair in a braid and answered questions the way engineers check code. We sat at a polished table with a carafe of water and a view of a sliver of harbor. I slid the prenup across. She read without fidgeting. When she got to the section most people skim, she smiled the way a person smiles when a weather report confirms what they suspected. “This protects his separate property,” she said, tapping the page with a capped pen, “and yours.” She met my eyes. “If you receive assets during marriage by gift or inheritance, those remain your separate property—unless you commingle in a way that changes their character. You haven’t commingled.”

“I opened a new account,” I said, and the quiet in me stood up a little taller.

“Good,” she said. “Don’t move it. And if you decide you’re done, we will be done precisely. You won’t owe him a dime.”

I walked out into the sun and the trolleys, into a city where people in Padres caps held iced coffees like talismans. I took a deep breath that tasted like sea salt and impatience. It wasn’t that I wanted victory. It was that I wanted gravity to apply equally.

I played the part they had written for me for a few weeks—the appreciative wife, the receptive daughter-in-law. I laughed when Adam said “Tahoe” as if he had discovered snow. I nodded when Evelyn mentioned Rancho Santa Fe like an afterthought. I moved numbers from a wire confirmation into a spreadsheet in a folder labeled with a name only I would ever guess. At night, I read case law until my eyes ached in that satisfying way good work makes you ache.

Adam’s phone is the reason some stories find their end. He showered with music on, steam catching the light like something important. His phone buzzed twice, a rhythm I’d learned to ignore. I didn’t snoop so much as glance. There it was: Sophia. A line that could be a joke, or a test, or a confession. I opened the thread and saw an archive of evenings. There were pictures that could have been proof or could have been cruel, depending on your mood. There were dates and places and language that told their own story without my help.

I didn’t cry. The part of me that would have cried was busy taking inventory: best practices, next steps, contingencies. I called a private investigator because there are times you need photographs taken by someone who knows how to photograph. He returned emails promptly. He sent me PDFs with dates in the corner. He delivered an annotated calendar that looked like a clean crime. I printed everything on a Saturday when Adam was at the gym with a friend who liked the kind of workouts that make noise. I placed the stack in a plain black folder and slid it into a tote beneath a sweater.

On Tuesday morning, I filed. Superior Court of California, County of San Diego, Family Law. My attorney met me at the clerk’s window, and we watched the time stamp find the corner of the petition like a period at the end of a sentence you’d worked too hard to write. The process server did his job. That evening, Adam came home with takeout and a story about a partnership that was going to change “everything” for his father’s company. I set the documents on the kitchen island—divorce papers on top, the prenup beneath, the photos in a separate envelope. He poured a drink. He saw the manila tab and blinked a blink that admitted displacement.

“What’s this?” he asked, which is what people ask when they already know and need you to say it.

“Read,” I said.

There is a transformation a face undergoes when the brain catches up to the page. It’s a sequence: confidence, curiosity, caution, calculation, then a sudden softening at the edges like a photograph taken at the wrong shutter speed. Adam flipped. He landed at the clause we’d all taken for granted while a notary adjusted the angle of her stamp three years ago. He read the words separate property and inheritance and not subject to division. He looked from the page to me as if eye contact could cause the language to reformat.

“You’ll get nothing,” he said, almost kindly, reminding himself.

“I’m not asking for anything of yours,” I said, and placed my finger on the line that mattered. “And you’re not getting anything of mine.”

Silence is honest when paper is on a table.

“Okay,” he said finally, laughing softly like a man in a lobby trying to charm a receptionist. “We’ll see.”

He called his parents. Of course he did. If you’re raised with a net, your first instinct is to fall and trust it. The next day, Evelyn phoned me, voice polished to a shine. “Darling,” she said, as if we shared a nickname. “Let’s not do anything rash.”

I waited.

“Adam is upset,” she continued. “You know how he can be. He’s not thinking clearly. Why don’t we all sit down with our advisor? There are smarter ways to… structure… things.”

“There are,” I agreed. “And we will structure things very smartly.”

When she realized she couldn’t coax me with her first voice, she tried her second. “You’ll regret this,” she said, the words flat against the handset.

“I already did,” I said. “Years ago, when I signed.”

They contested the prenup, because sometimes the only strategy left is to argue the rules you wrote should not apply to you. Their attorney filed a motion that used the kind of words people use when they don’t want to say what they mean: unconscionable, duress. They wanted retroactive mercy for a document they’d had the luxury of time to craft. My attorney smiled and said, “We’ll bring a flashlight.”

The hearing day arrived like any other day: traffic, coffee, a woman outside the courthouse wearing a denim jacket with an embroidered eagle across the back. The judge assigned to our case had the kind of posture you get when you’ve seen every version of “this will only take a minute.” Adam sat at counsel table with two of his parents’ lawyers and a legal pad he never wrote on. Evelyn wore navy and a string of pearls that didn’t catch the light. Richard adjusted his watch as if time would cooperate. I sat with my attorney and a forensic accountant named Neil, who had the serene, careful look of a person who knows how to find a decimal that wandered off in 2017.

Evelyn’s attorney stood and tried to rearrange the meaning of the word fairness. He spoke of families and expectations and the spirit of agreements. He said the document hadn’t been explained to me thoroughly enough, as if I hadn’t spent my adult life explaining complicated things to men in conference rooms. When he finished, my attorney stood and gently returned every word to its definition. She placed a thin folder on the lectern and reviewed the timeline—the drafts, the notary, the delays for edits his family had requested. She pointed to my profession in a single sentence, not to brag, but to anchor. Then she nodded to Neil.

Neil didn’t clear his throat. He clicked a button on a small remote and a monitor beside the bench woke into blue, then white, then numbers. He walked the court through a simple story: a row of invoices that had been paid to a shell company with a name nearly identical to one of the real ones, deposits that landed in a private account, a line in a spreadsheet miscategorized as “promotional housing,” a signature that repeated itself too perfectly across months. He kept his voice level, as if he were explaining a recipe to someone who could cook.

“Your Honor,” my attorney said, “before we discuss whether a freely signed agreement is somehow unfair, we need to ask a more immediate question: what is this?” She tapped the report. “And why is the executive listed here”—she circled a name that was our family name—“signing off?”

Evelyn’s face went still the way an actor’s face goes still right before an intermission. Richard’s jaw locked. Adam blinked as if the screen were too bright. The judge leaned forward the way people lean when a plane begins to descend. He didn’t make a speech. He asked four questions, each perfectly aimed. He took the binder my attorney offered and read three pages without appearing to blink.

“We will not be voiding this agreement,” he said, finally, and his voice filled the room with climate control. “As to the other issues raised, I’m directing counsel to confer with the appropriate agencies.” He looked at the attorneys as if he were taking attendance. “This proceeding is about dissolution. But if numbers are being misrepresented in filings before this court, we will not pretend that isn’t happening.”

Everything after that is process, and process is quiet. The prenup stood. My inheritance remained untouched. The account I had opened remained solely mine, the way a new door remains a new door even if the rest of the house is old. Evelyn and Richard’s company met a kind of scrutiny it hadn’t requested. Letters arrived with seals. Accounts that used to move the way a tide moves met a low, investigative moon. The people who used to call Evelyn back in five minutes began to reply, “Let me check,” and then stopped replying altogether.

Adam tried anger first and found it exhausting. “You set me up,” he said, the way a child says “You started it” when the teacher steps into the hall. When that didn’t work, he tried contrition. “We can fix this,” he said, texting me photographs from the early days like a person who thinks memory is a coupon code. I didn’t reply because I didn’t owe a reply. My attorney handled messages at the pace paper requires.

Sophia called once from a number I didn’t recognize and practiced her own version of anger on speakerphone. “He said we’d have everything,” she snapped, as if I had closed a bank branch out of spite. “He said there was a plan.”

“I’m sure there was,” I said, keeping my voice level. “It just wasn’t mine.”

After the hearing, I moved into an apartment that looked directly at the ocean as if it were a habit. It wasn’t a statement. It was a correction. I paid in full. The escrow officer congratulated me with a handshake that felt like respect. The day I carried my first box across the threshold, the porch flag of the building across the street struck once in the wind like a bell. I stood in the doorway and let it ring in my bones.

I furnished the place slowly. A blue sofa that could hold a whole Sunday. A table with a wood grain that looked like weather. Plants that forgive. A kettle that sings. While the legal process finished its work, I finished mine. I took long walks past houses with mailboxes that could have swallowed my first apartment whole. I learned the tide schedule because you should learn the patterns of the places you love. I found a little coffee shop where the barista had a tattoo of a paper airplane on her wrist and a memory for names, and I tipped too much because kindness deserves to be paid like labor.

On paper, my life divided into columns that made accountants proud. In practice, it braided together into something strong: work I liked, a view that didn’t apologize, friends who knew how to show up, a plan. I started a small fund for women in my field who had ideas and not enough runway. I named it after my uncle, the quiet banker whose careful life had given me a door. I set up scholarships at my state school for first-generation students who wanted to study computer science, because the world is a better place when people who know how to build get funded to build.

One afternoon, months after the hearing, my attorney forwarded a letter about the company investigation with the kind of short preface good lawyers prefer—FYI. It was clinical as a weather report, and as consequential. There would be more questions for Evelyn and Richard. There would be more numbers to locate. You could feel the weight shifting again, not because anyone shouted, but because the rules were being applied in the order they were written.

Adam eventually signed the final documents because there wasn’t another plausible verb. His last message to me was three lines long and ended the way a problem statement ends, without a solution. I didn’t respond. I didn’t need to. The story didn’t require another scene with him. Not all arcs are meant to be reconciled. Some are meant to close.

On the morning my divorce became final, the clerk stamped the judgment and handed my attorney a copy that felt lighter than paper should feel. I walked out into Civic Center Plaza with the sun off the glass of the buildings and the smell of food trucks settling like a promise. I sat on a bench and called my mother. We talked about work and the weather and the peonies in her yard back home. We didn’t talk much about Adam. We didn’t need to. Some names stop being nouns and return to being sounds: air out, air in.

The next day I woke up in a room that belonged only to me and made eggs the way I like them. I carried my plate to the window and watched a runner in a navy windbreaker move along the sidewalk like punctuation. Freedom is rarely dramatic. It’s a series of small permissions you grant yourself: another cup of coffee, another hour with a book, a walk without telling anyone where you’re going, a budget with one signature.

Evelyn asked for a meeting, months later, when the consequences began to line up like appointments she couldn’t skip. We met at a neutral café in Del Mar with bright chairs and the kind of pastries that require you to commit to a fork. She wore a jacket I had only ever seen at events with name tags. Her hair was precise. She started to say something and then stopped. The manager changed the station. The flag outside the café caught and unrolled and caught again.

“I didn’t want to dislike you,” she said finally, like someone who has practiced for an apology but not its aftermath.

“I know,” I said, because I did. Wanting is not the same as choosing.

She asked if there was a way to “soften the optics,” and it was a relief to hear her ask exactly the question she meant. “There’s a way to tell the truth,” I said, “and let the chips fall where they fall.”

She nodded once, the way people nod when they are practicing acceptance. She looked at the table, at her hands, at the door. “I told myself I was protecting him,” she said, and for a second the woman who had once rearranged my sofa pillows looked like someone else—a mother with a story she couldn’t edit.

“You were building a world where he didn’t have to grow up,” I said gently. “That’s not protection. That’s permission.”

She closed her eyes. When she opened them, they were red at the edges. She didn’t ask for forgiveness; she asked for water, and I got up and got it, because mercy is a kind of cleanliness you keep for yourself as much as for anyone else.

I didn’t crush them in court. I didn’t dance on any graves. I honored the process and told the truth and let professionals do the job citizens hire them to do with taxes and trust. Justice isn’t spectacle; it’s alignment. It’s a judge remembering the word agreement means something. It’s an accountant who cares about decimals the way other people care about weather. It’s an investigator who files without adjectives. It’s me, standing in my kitchen, highlighting a clause written in black ink years ago and letting it do precisely what it promised.

By fall, the air had that clean feel mornings get in Southern California, when the heat backs down and the sky is the right kind of blue. I joined a volunteer legal clinic that hosts free Saturday sessions about contracts. We don’t tell people what to sign or not sign; we teach them how to read. On my first morning, a young woman came in with a folder and a tight mouth and said, “It’s probably nothing.” I smiled and slid a highlighter across the table. “Those are my favorite kinds of somethings,” I said, and we began.

My home has its own customs now. I keep the windows open on nights when the water is loud because the sound is an honest soundtrack. I make a big pot of soup on Sundays and give half to the neighbor in 3B who is studying for his citizenship test and asks me practice questions about branches of government that refresh my faith in paperwork done properly. On the Fourth of July, I watched from my balcony as the beach lit up in a choreography that always makes me cry for reasons I don’t need to explain. The little flag that hangs on the railing in my building’s entry rustled like a whisper.

Work is good. Life is good. I say that without triumph because goodness is not a scoreboard; it’s a set of habits. I still write code with a pencil tucked behind my ear because old motions die slowly. I run along the water before the sun forgets it’s morning because discipline is a kind of love. I call my mother on Thursdays because rhythms keep us whole. I am careful with my money not because I’m afraid it will vanish, but because stewardship is a way to say thank you to time.

Once, months after the divorce, I saw Adam across a street downtown, outside a building where people stand when they are pretending to wait for someone else. He looked like a man who’d finally met his own reflection and had accepted that mirrors tell the truth whether you ask kindly or not. He didn’t see me. I could have crossed. I could have said hello and found a polite sentence to toss across the past like a blanket at a picnic you don’t intend to stay at. I didn’t. Not out of meanness. Out of respect—for endings, for clean cuts, for the life I was crossing back toward.

In the end, nothing I did was extraordinary. I read a document I had signed. I opened a bank account. I hired competent people. I told the truth. I left. That’s all. It’s the kind of all that changes a life.

I finished unpacking months ago but I still occasionally find a small thing at the bottom of a drawer—a roll of measuring tape, a packet of seeds from the nursery on Rosecrans, a note I wrote myself three years ago that says simply: choose yourself. I tuck it back in the drawer because reminders should live where you reach for them.

On a clear evening in November, I set two glasses on my table—one for me, one for a friend who was coming over with the kind of laughter that makes rooms warmer. The sun went down red and then orange and then the pale gray that belongs only to the stretch between dusk and night along this coastline. The flag across the street lifted and settled and lifted again. I turned on a lamp and the room shifted into its soft version.

Justice had not punished my enemies. It had protected my rights. That’s the promise we live under, if we’re lucky and loud enough to insist on it. Evelyn once told me I’d regret leaving. I don’t. I regret the years I believed that being loved by them would mean being safe with them. Safety isn’t something people grant you; it’s something you build—policy by policy, clause by clause, boundary by boundary, door by door.

When my friend knocked, I opened the door to a woman whose arms already knew where they were going. Behind her, the corridor held a neat line of welcome mats, each one announcing a different sense of humor. We ate soup and told the kinds of stories that make the world both truer and lighter. At the end of the night, I stood at the window alone for a moment, letting the quiet do its work. A car passed. A siren far away found then lost itself. The ocean kept at it. I wasn’t waiting for anything. My life had arrived.

People sometimes ask me now—at the clinic, at work, at dinner—what I’d say to someone staring at a page with a line that says “This is Adam’s house.” I’d say: read the next line. Read the section past the one they point at. Read until you find the part that keeps you whole. Then sign or don’t. But if you sign, sign with your eyes open and your own pen. Keep copies. Keep counsel. Keep yourself.

And if the day comes when you realize the house you live in is a story that refuses to let you be the main character, then open a new door. The world will look different at first. Then it will look like yours.

That’s my ending. Not fireworks on a courthouse step. Not a headline. Just a woman in San Diego, in a small, beautiful home that answers to her name, stirring soup, checking a lock she paid for, watching a flag twitch in the ocean air, grateful for a system that—on a good day, on a fair day—lets paper keep its promises and people reclaim their lives.