The night I pressed record, the house drew breath like it had a secret to keep.

The night I pressed record, the house drew breath like it had a secret to keep.

I was standing barefoot in the hall of a two-story Colonial on the quiet edge of Salem, Massachusetts, the kind of neighborhood where you can hear Friday-night drums from the high school and see a blue USPS box from your kitchen window. My phone screen showed Room 204 upstairs—my mother-in-law’s room—lit in soft amber, walls crowded with Mercer family photographs and a small wooden metronome ticking at a pace the microphone barely caught. In the frame, my husband sat forward on a low ottoman, hands on his knees, eyes focused past the shoulder of the woman who raised him. She spoke in a steady voice I had never heard addressed to me, a cadence flat and careful, like a recipe read by someone who doesn’t need the card. He answered almost in time, as if the words were choreography he’d learned long ago, steps that never changed even when the music did.

I am Nora Bennett, twenty-nine, a transplant who still pronounces the r in car and tips too much at Dunkin’ because the kid at the counter remembers my order. I married Ethan Mercer because he felt like the steady part of a storm. He was thirty-two then, polite to a fault, the kind of person who keeps jumper cables in his trunk and wipes the snow from a stranger’s windshield at stoplights. He listened the way architects like me draw—deliberately, with attention to edges. Our first year, when people asked how married life was, I told them about the hydrangeas on the side yard and how the old floors creaked in the afternoon like the house was settling into its bones. I did not tell them that Ethan never reached for my hand. I did not mention that each night ended with the same almost—his gentle smile, his apology, the soft click of a door I was not invited to enter, and then his return twenty minutes later with a look I learned to read as jet lag in his own home.

“Maybe tomorrow,” he’d say, and that sentence fit neatly in a kitchen drawer with expired warranties and rubber bands no one uses. Tomorrow lingered like fog on Derby Street, thickest when the sun tried hardest to burn through.

It started small, the way long winters do. A brushed shoulder. A turned cheek. The fine grit of distance collecting in the corners of a life that otherwise looked good on paper. We planted tomatoes. We filed taxes early. We hosted his mother, Marjorie, for Red Sox games she never actually watched. She lived with us, technically; 204 was her door—locked when she left, knocked upon when anyone entered, even her son. She kept her earl grey tea bags in a glass jar and ironed pillowcases so flat they felt like hotel sheets. When I asked about the lock, Ethan smiled with a kind patience I once mistook for assurance. “It’s just her space,” he said. “She’s always been private.”

The house loved New England rituals. On the Fourth of July, a little flag stuck up from the planter on the porch. In October, the air sharpened and Salem filled with out-of-towners wearing witch hats who asked for directions to the museums. In December, the radiators hissed and a strand of lights along the porch rail flickered out and back the way all old things do when they want you to notice them but not panic. What I did panic about stayed private. When friends leaned across café tables and asked how we were, I fed them logistics. Work’s busy. We’re painting the dining room. Either the brush in my hand or the list in my phone could fix whatever felt off, I told myself. I was wrong.

Marjorie had a way of smiling that looked like a compliment until you thought about it later. “Ethan checks on my medication,” she would say lightly, like mentioning the weather. “He’s very good.” Her hand would find his forearm. His eyes would flick to 204 and back to me. And I would say something kind because I was raised to add sugar first, even when the water never warms.

When her doctor recommended a home-monitoring system—motion alerts, fall detection—Marjorie agreed with a graciousness that made me feel ungrateful for hesitating. “Strictly for safety,” she said. “You never know.” I installed it because I am the tech-savvy one—the routers, the thermostats, the printer that only likes to work on Tuesdays. The cameras were discreet under crown molding, even the small lens in 204, justified for health. I tucked the app into a folder on my phone between Weather and Notes. The entryway camera caught a reflection of the flag magnet on our fridge at certain hours, and it made me oddly steady to see it there in miniature, like a reminder that houses can be complicated and still be home.

The pattern announced itself before I believed it. Pings at two-hour intervals, mostly after dinner, sometimes late enough that the street was a map in sodium-yellow. My phone would buzz, and I would imagine Ethan’s footsteps in the hall, those exact two knocks on 204, the click, the brief hush, the twenty minutes, the quiet return. The look he brought back was peculiar—a careful blank. Not sadness, not anger. Like someone waking mid-flight, unsure how many time zones had passed underneath.

The night I opened the app, I told myself I was doing something decent—checking on health, on safety, on an older woman with a stiff hip and strong opinions. Ethan had gone to the garage. From the doorway I could hear Boston sports radio arguing about a reliever’s ERA like lives depended on it. The December wind found the seam on the back door and whistled a small warning. I stood at the kitchen island, between the flag magnet and a bowl of apples we never finished, and tapped Room 204.

Marjorie sat upright in her high-back chair, hands folded, posture polite the way people make it when cameras exist. Ethan perched on the ottoman. No pill organizers. No charts. Just the metronome. Tick. Tick. She started. Short sentences, level tone. He answered. Soft. Measured. The tempo between them was so exact it made me aware of my own breath—how it stuttered when I realized I was watching something I was not meant to see, how it steadied when I told myself knowledge is better than darkness, even when it hurts.

The words themselves didn’t carry to me fully—the microphone was reading a room that had learned to control sound. But the pattern was clear. She posed statements like mile markers; he acknowledged them and moved along. I wasn’t hearing medicine reminders. I wasn’t hearing comfort. I was hearing rules rehearsed, compliance refined by practice. The direction of care ran uphill, against what I thought I knew of mother and son. It was choreography. And if you think choreography is innocent, you’ve never seen what it can become when one partner chooses the music forever.

I pressed record. I watched and hated myself for watching and couldn’t stop because once a secret speaks, you find out what it says or it owns you. My hand shook. My other hand found the counter. I stood still the way you do at a one-lane bridge when the sign says YIELD and you think you were there first but maybe you weren’t.

When it ended—twenty minutes almost to the second—Ethan set the metronome back a quarter inch, as if alignment mattered. He left the room with his polite face on. He passed me in the hall, kissed my temple like I was something delicate you place on a high shelf, and went to the kitchen to rinse a mug he hadn’t used. I said nothing because I was practicing how not to cry yet.

The next morning, I ran along the harbor until the gulls’ complaints drowned out everything else. Back home, I made a list titled QUESTIONS and added nothing under it. I spent an hour reading Massachusetts law badly and called no one. That night, the pings resumed. When you see a pattern, you can’t unsee it. When you know the number is two hours, the waiting fills those hours exactly.

It took me three days to speak. I chose a Saturday afternoon, sunlight low and gold on the dining room’s old wainscoting. Marjorie was at the market; she’d left a note on the counter in neat script: lemons, newspaper, stamps. I put my phone face-down. The recordings, gathered over a handful of days, sat inside like proof you hate to own.

“I watched the 204 camera,” I said.

It was the first time I had entered Room 204, even if only by proxy.

Ethan didn’t pretend to misunderstand. His jaw went soft in the way it does when he’s trying to hold two truths and not let either fall. He was tired, the kind of tired a nap can’t touch.

“I don’t know where to start,” he said.

“Start by telling me what it is,” I said, because naming is the first carpenter’s cut when you’re trying to make a life.

He looked at the doorway to 204 like it might overhear us. “When I was a kid,” he said, “my dad traveled. My mother had… routines. She called them anchors. She said they kept the house safe. She taught me to help. It was a kindness at first. A job for us. But it didn’t stop. When I got older, the anchors got… stricter. After college, after Dad died, she was alone and I thought coming back was the right thing. The anchors—” he searched for a word that wasn’t a confession “—they became the way we talked. The only way, sometimes.”

“Choreography,” I said, and he flinched like I’d said a private password out loud.

“It isn’t—” He stopped, reconsidered. “It hasn’t been right for a long time. I didn’t know how to get from here to not-here.”

“You walked past our door,” I said. It came out smaller than I intended. “Every night.”

He rubbed his forehead with two fingers. “I told myself I was choosing mercy. She believes the rules keep everything from unraveling. If I did them, then the day ended quietly. If I didn’t, she—” His hand hovered, then fell. “You saw what I am like when I come back.”

“What she is like when you don’t?” I asked.

He looked at me with old loyalty and new shame. “She is… formidable.”

“Did you ever think to let me in?” I asked. I didn’t mean 204.

He closed his eyes. “I kept thinking tomorrow. That I’d handle it before you had to know. I’ve been saying tomorrow since I was thirteen.”

We were very quiet for a long time. Cars passed on the street. A neighbor dragged her trash barrel to the curb. The house did its familiar winter sigh. Sometimes the only thing to do with a map that turns out to be wrong is set it down and sit with the blank. I put my hand on the table between us, palm up. After a breath, he put his hand in mine.

“What do we do next?” he asked.

“We stop calling it normal,” I said. “We stop pretending this house works. We ask someone who knows about anchors how to cut rope.”

We started with a therapist who had a sensible office near the Common and a way of listening that didn’t feel like surveillance. Dr. Isla Hart. She didn’t make our sentences sound stranger than they were, which gave me confidence she’d heard worse and better and was not interested in theater. Ethan said the word patterns in a tone that made me remember every time he had tried to be a good son and a good husband and failed at both because the rules were designed that way.

Dr. Hart called it coercive structure. She said it can dress up as duty and care, and that some children grow into adults who mistake compliance for kindness because that’s how they kept a parent happy. She talked about boundaries like door frames. Strong ones keep the house safe. Doors without frames slam and splinter. She eyed the recordings I’d brought on a secure drive with the caution of a person who understands both the value and danger of proof.

“Here’s what I hear,” she said carefully. “A ritualized, repeated form of interaction—a script that maps his nervous system. It may have started as soothing. It’s now the only road he’s allowed to drive on. We need to build a new road.”

We went twice a week. Ethan sat with his shoulders forward, as if braced for impact, then slowly let each muscle learn that a chair can hold more than weight. I learned where my patience ended and where my loyalty began. We built sentences that could survive a storm.

We also spoke to an attorney, because some kinds of justice require paperwork. Marta Delgado was brisk in a way I found comforting; she wrote letters that sounded like steel wrapped in linen. “You are not being unkind,” she said when I apologized for nothing in particular. “You are being clear. Clarity saves everybody time.”

Marta drafted a notice delineating household boundaries: no closed-door meetings without both parties’ consent; no interference with marital privacy; all “health checks” to be managed with third-party home health aides. She included a summary of what Massachusetts calls harassment prevention, not because we wanted to run there first, but because naming options makes a person stand up straighter. She read the letter aloud to us before sending, and I realized how often we had narrated our lives in soft focus. This was the opposite, and it was necessary.

We showed the letter to Ethan’s mother at the kitchen table. She poured tea and added sugar with the graceful economy of a person who has measured sweetness a long time.

“Darling,” she said, not looking at me, “this is unnecessary. Ethan understands our routine. It gives me peace. Doctors say routine is good for the older mind.”

“Doctors also say routine shouldn’t replace respect,” I said. “We’ve arranged for a home health aide on Tuesdays and Thursdays. She can sit with you, check your meds, help you organize 204.”

Marjorie’s mouth twitched, then went still. “I don’t need a stranger in my room,” she said. “I have my son.”

“The aide isn’t a stranger,” Ethan said quietly. “She’s a professional.”

Marjorie’s eyes found his. For a second, the house leaned. “You won’t let them,” she said to him, skipping my existence like a pebble. “Tell them you won’t.”

Ethan reached into his pocket and pulled out the metronome key. He set it on the table and slid it toward her. “I love you,” he said. “But I’m not doing that anymore.”

There are sentences that shift climate. The kitchen got smaller and brighter at once, like someone opened a window we didn’t know was painted shut. Marjorie looked at the small piece of metal like a foreign coin. She did not reach for it.

“After all I’ve done,” she said, voice fluted with disbelief. “After all my care.”

“You cared in the only way you knew,” Ethan said, and the kindness in his voice ripped me open. “It doesn’t work anymore.”

She stood very straight. “We’ll talk about this later,” she said, which is what people say when they are used to later favoring them. She did not look at me as she went upstairs.

Later did not favor her. A home health aide named Linda arrived Tuesday—cheerful, unafraid of old houses, competent with pill organizers. Marjorie accepted her in the frosty manner of someone who cannot complain about the soup because everyone else has already said it’s good. The first day went fine. The second day lasted thirty minutes before Marjorie sent Linda away with a temperature only New England politeness measures.

“Let’s try again Thursday,” Linda said to me, eyes understanding more than she said. “Some folks have to practice accepting help.”

That night, the two-hour ping did not come. I sat on the couch watching a rerun of a cooking show where a chef saved a broken sauce by starting over bravely. At 10:02, my phone vibrated. I stared at it and didn’t tap. Ethan sat beside me, knee touching mine, like a bridge he remembered how to cross. We let it ring and then go quiet. The quiet made its own sound.

When you change a rhythm, the old rhythm tests the weak spots. We anticipated resistance. We did not predict the precision. A week later, on a Sunday afternoon with football in the background and the roast resting on a cutting board, Marjorie asked Ethan to bring her a book from 204. He hesitated and then went, because a book is a book and this is how compromise starts. Ten minutes passed. Fifteen. The house’s air got that bright thinness again. I stood outside 204 and heard nothing except my own blood in my ears. I knocked. The door was unlocked. I stepped in.

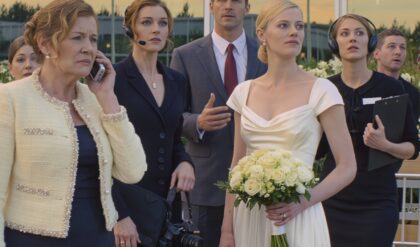

The room was clean, careful. Photographs, freshly dusted. Curtains open to the winter sun. The metronome sat on the dresser, still. Marjorie stood with her back to me. Ethan sat on the ottoman. His hands were on his knees. He looked at me like a diver breaking surface—surprised at the light, desperate for air.

“Knock before you enter,” Marjorie said, level as ever.

“I did,” I said. “We’re going downstairs.”

“This is not your room,” she said.

“It’s not your son’s either,” I said, and the words felt like a tool finally used for its purpose. I walked to Ethan and held out my hand. He took it instantly, a muscle memory from a different life emerging at the exact right time. We left 204 together.

Marjorie followed to the hall and said his name in a voice I had heard only over the speakers of a camera before. Ethan stopped. For a moment, the old choreography looked like it might pull him back into the room. The house held its breath with me.

“Mom,” he said softly, but firmly, a word he had said a thousand times dressed differently now. “No.”

We closed our bedroom door and leaned against it like a pair of fugitives safe at last. He laughed once without humor and then cried, the kind that robs words of their usefulness. I stood with him, our shoulders touching, and found that some doors open only after others close.

Boundaries are not punishments. They are road signs that prevent collisions. We made more of them. We replaced the lock on 204 with one that clicked open from the outside so a health aide could enter in emergencies. We hired Linda full-time with the help of a state program Dr. Hart told us about. We moved Marjorie’s evening tea downstairs. We sat together for dinner at a time announced each afternoon like a train schedule. Some nights, she joined. Some nights, she refused and muttered about independence. We did not chase her with our old apology.

January brought snow, the heavy kind that erases sidewalks and gives kids a reason to love Maine’s winter even from Massachusetts. I shoveled twice before dawn while Ethan salted the steps. When I came in, the house had a different silence—expectant, not punitive. We drank coffee standing by the back door, the flag magnet holding a grocery list that said milk, bread, courage.

The first time Ethan slipped his hand into mine at the sink, it felt ordinary and miraculous. The first time he kissed me, it felt like a promise made good quietly, the way good promises prefer. We did not fix three years of absence in a week. We did not pretend the human nervous system is a circuit breaker you flip up and down. We went to therapy. We walked after dinner regardless of weather. We learned how to say “I’m overwhelmed” before either of us acted like it. He kept a journal the color of a storm cloud and wrote in it every morning. I worked later at the office because sometimes building a house in my head was easier than living in one under repair. We slept better. We kept our door shut without shame.

Marjorie did not go quietly, because the old ways fought for their lives. She tried to corner Ethan in the laundry room with “one quick check.” She attempted to schedule his time out loud in front of me, a tactic that only works if the witness refuses to interrupt. I interrupted politely and repeatedly, like a metronome of my own, and it drove her wild in a way she mostly hid.

The day everything shifted for good was a Thursday in March when the light finally lasted past five. Linda called me at work. “Mrs. Bennett?” she said, though I hadn’t asked her to stop calling me Nora. “We’ve had a moment here.”

I got home to find Marjorie at the kitchen table with her calendar, face pinched, hands twisting a tissue into a rope. Ethan stood with his back to the fridge like he might push it to a different wall to change the layout of the problem. Linda met me at the door and spoke low.

“Your mother-in-law called a neighbor to say she was ‘not allowed to see her son,’” she said. “The neighbor called the non-emergency line. Two officers came and asked questions. It escalated for a moment. Everybody is fine. They left after hearing your husband explain the plan and after I showed them the care plan.”

I breathed. “Thank you.”

Linda squeezed my arm. “She needs structure. You’re giving it. That’s harder than giving in, but less cruel.”

I sat at the table across from Marjorie and folded my hands the way she does, not as mockery but as truce. “We need to make a bigger change,” I said. “For all of us.”

She looked beyond me to her son as if the answer still lived there. It didn’t.

“The house is old,” I continued. “It keeps secrets too well. We’re going to sell it and find two places. One for us. One appropriate for you. An apartment near your church. You’ll have aides and neighbors. We’ll have a home where our marriage is the first routine.”

“You can’t—” she started, then went quiet when she saw the letter from Marta on the table with the words purchase and sale bolded like a drumbeat.

“We can,” Ethan said gently. “We’re under contract already.”

We’d put the Colonial on the market on a Tuesday and by Friday a young family with a golden retriever named Tank had offered over asking. I sighed when I saw the name because Tank felt like a dog who would put his head in your lap on bad days.

Marjorie folded the tissue once, then again, as if she could condense change into something that would fit in her pocket. “This house is mine,” she said.

“It is ours legally,” Ethan said, “and it has never actually belonged to me.” He touched the table like blessing a ship. “It has been a port. We’re sailing.”

She did not bless us. She did not curse us either. She stood up and went to 204 with an upright dignity I understood. Linda followed to help her pack photo albums into boxes labeled with thick black marker—Keep, Donate, Ask Ethan—because asking is a skill you learn last.

The closing was in April on a rainy Wednesday that made umbrellas look like dark flowers blooming. We signed papers at a long table on the twenty-first floor while the city ran its errands below. The buyer couple smiled, young enough to believe every new house is entirely new. Ethan handed over the key with the brass tag stamped 204. He did not wince. We took only what we needed. We had learned how much this was.

We moved into a light-filled second-floor apartment in Marblehead with a view of a sliver of harbor if you squinted between rooftops. The first box we opened held two mugs and a small flag on a wooden stick that had been stuck behind our old bookshelf like a lost suggestion. I put it in a planter on the new porch because beginnings like symbols. We ate pizza on the floor because that is what you do when you are happy and broke and not quite either.

The first night there, sleep found us at the same time. I woke at 2:04 out of habit and watched the ceiling glow faintly from the streetlight outside. Nothing pinged. No footsteps. Just Ethan breathing next to me, the ordinary miracle of a man asleep beside his wife.

Marjorie’s new apartment was near her church and a bus stop she could reach without stairs. Linda helped her assemble a bookcase and stocked the pantry with tea. We set up her medication with the pharmacist’s help. We posted a schedule on the inside of a cabinet door and framed it as choice, not order. We visited on Sundays with muffins from a bakery that sells them still warm. Some visits were gentler than others. We left when the temperature dropped. We learned that love can look like leaving early to protect the part of a relationship that can still grow.

Spring slid into summer slowly, as if the season had a limp. In June, the therapy office got too warm and Dr. Hart apologized and clicked on a fan. Ethan unlearned more than he learned. It’s odd to describe relearning the natural. He put his phone in a drawer after work. He asked me questions with curiosity unstiffened by fear. We touched without asking ourselves what we were allowed. Some nights we fell asleep on the couch, sunlight still on the edge of the rug. I started running later, when the harbor smelled like warm rope and salt, and I came home to the clink of two bowls because he finally made dinner while listening to a podcast about old stadiums turning into parks. He told me he’d always wanted to say grace but only knew the kind that was half apology. We made one of our own: thank you for the floor that holds, the roof that doesn’t leak, the hand that keeps showing up.

July Fourth brought a parade down the main street small enough to feel like a joke at its own expense. Kids with streamers. A fire truck, red as certainty. Little flags everywhere, copying one another cheerfully. We set out folding chairs and watched people we didn’t know wave at us like we did. After, we grilled on a borrowed hibachi on the porch and called it a victory because it was. Marjorie came by for lemonade. She looked smaller in the summer light, not diminished, exactly—contained. She sat for twenty minutes and told Ethan a story about his father I hadn’t heard yet. The edges of it were gentle. When she stood to go, she patted my hand once like a woman reminding herself how.

In August, we bought a used station wagon with the kind of cargo space that makes hardware store workers nod at you as if you understand lumber. We painted the living room a color named Harbor Fog that made the morning feel like it chose the room. We argued about nothing, about something, about where the wall art should go, and then laughed at ourselves, because the worst thing about a house that was wrong is you forget how normal petty fights can be. We remembered.

In September, Ethan met with a counselor who specialized in family systems for six sessions of what he jokingly called de-programming until he stopped joking because there was nothing to be embarrassed about anymore. He wrote a letter to Marjorie with Dr. Hart’s help, one that honored the parts of their history that held without pretending the broken bits were vintage. He read it to me on the couch, stumbling once on the word mercy because sometimes mercy is heavier than justice until you carry it with someone else.

We were sitting in a splinter of sun on a Saturday morning in October when we decided to throw a small party. Not to celebrate the end of anything. To mark a beginning already underway. We invited neighbors who had lent us sugar and a drill, Linda and her sister, Marta who had bulldozed paperwork so we didn’t have to, Dr. Hart (who politely declined and sent a card that said Proud of the work in tidy script), and three friends who had listened without flinching while we learned a new language for our life.

I strung lights across the porch. Ethan set up a Bluetooth speaker that refused to pair in the obstinate way of all Bluetooth devices; he coaxed it into compliance by sheer niceness, which is his method. People arrived with dishes—corn salad, brownies, a pasta that tasted better because it was eaten standing up outside. Someone set a tiny flag in a jar near the drinks without comment and the sight of it made my throat tight because sometimes a symbol can be unassuming and still know its job.

Marjorie came, late, in a navy cardigan and good shoes. She handed me a paper bag with lemon bars and a brittle apology tucked into the corner like a napkin. “Thank you for inviting me,” she said.

“You’re family,” I said, and those two words behaved themselves.

She watched us for an hour, quietly, the way a person watches the ocean they once thought they commanded. Before she left, she touched Ethan’s cheek the way she did when he was a boy. “You look well,” she said. “Keep whatever you are doing.”

“We will,” he said.

Winter arrived the way it always does here—one morning the wind had teeth. We bought a tree from the lot behind the library and decorated it with ornaments that did not match on purpose. On Christmas morning, we went to Marjorie’s and made pancakes on her hot plate because her stove works but shouldn’t. She gave me a framed photograph of me and Ethan on our new porch, printed from her phone. In the corner of the frame, a little flag leaned against a pot of mums, and the sight of it made me laugh. She smiled too. We cleaned up together in the kind of quiet that finally felt like peace, not a truce waiting to fail.

On New Year’s Eve, we stood in the kitchen and wrote three lines on a piece of paper we taped inside a cabinet: kindness first, clarity always, no more secret maps. We kissed at midnight and it tasted like champagne and relief and the ordinary sweetness of being where you belong.

When spring came around again, we drove past our old street. The family who bought the Colonial had set out chalk for their kids on the walk. Tank, who is as big as a small motorcycle, sat on the porch with his head exactly where I expected it to be—on someone’s lap who needed it. The new owners had painted the trim without stripping its history. Room 204 had become a guest room, I heard later. That detail felt like a proper spell broken.

People imagine happy endings are banners unfurled, brass bands, confetti. Ours is the smallness of daily life restored and enlarged. It’s my husband making coffee and setting the cup by my laptop without comment. It’s me leaving him a note on the fridge under the flag magnet that says back soon, love. It’s the sound of his feet in the hall at ten p.m. turning toward our door, not away. It’s a house that doesn’t keep secrets better than people do.

Every now and then, the old pattern rattles the doorknob, curious. It finds the door locked and the frame strong, then it goes. On the days it presses harder, we say our rules out loud like a recipe we do know by heart now. Kindness first. Clarity always. No more secret maps.

If you’re waiting for justice, wondering what it looks like when it finally arrives—sometimes it’s paperwork and a key slid across a table. Sometimes it’s a word spoken in a tone that does not shake. Sometimes it’s a chair pulled up to a new table, an extra plate set because you are brave enough to keep what’s good and refuse what isn’t in the same breath.

We are okay. More than okay. We are what happens when a door finally opens in the right direction and you walk through together. And when the house draws breath now, it’s only because someone left a window up to let in the salt air.